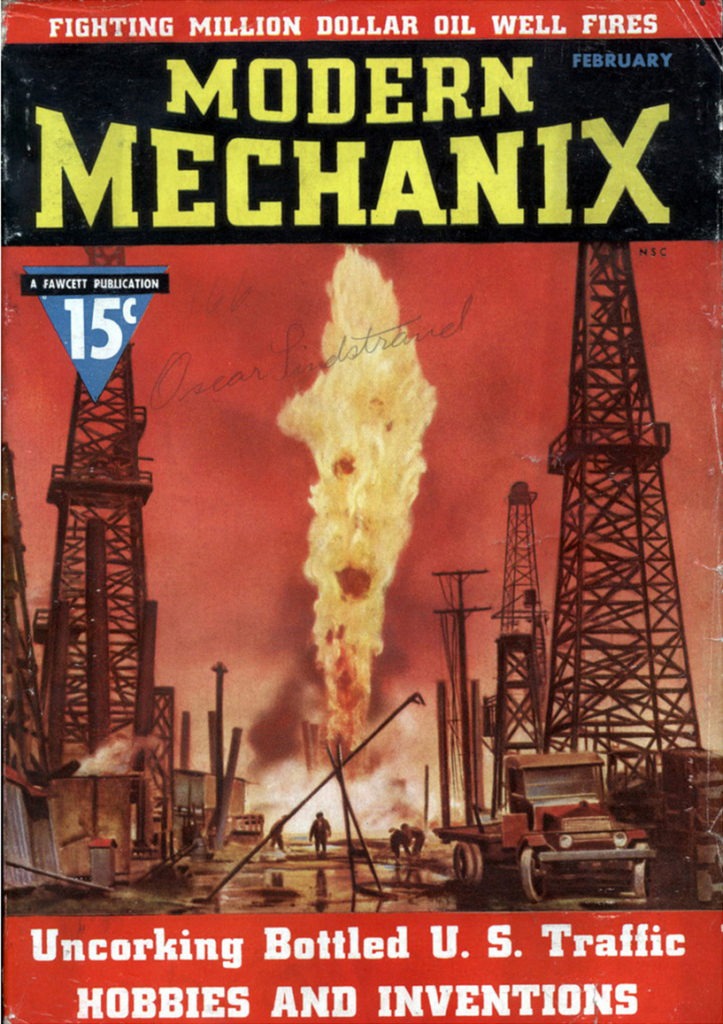

Modern Mechanix

ROMANCE Of The TIN CAN

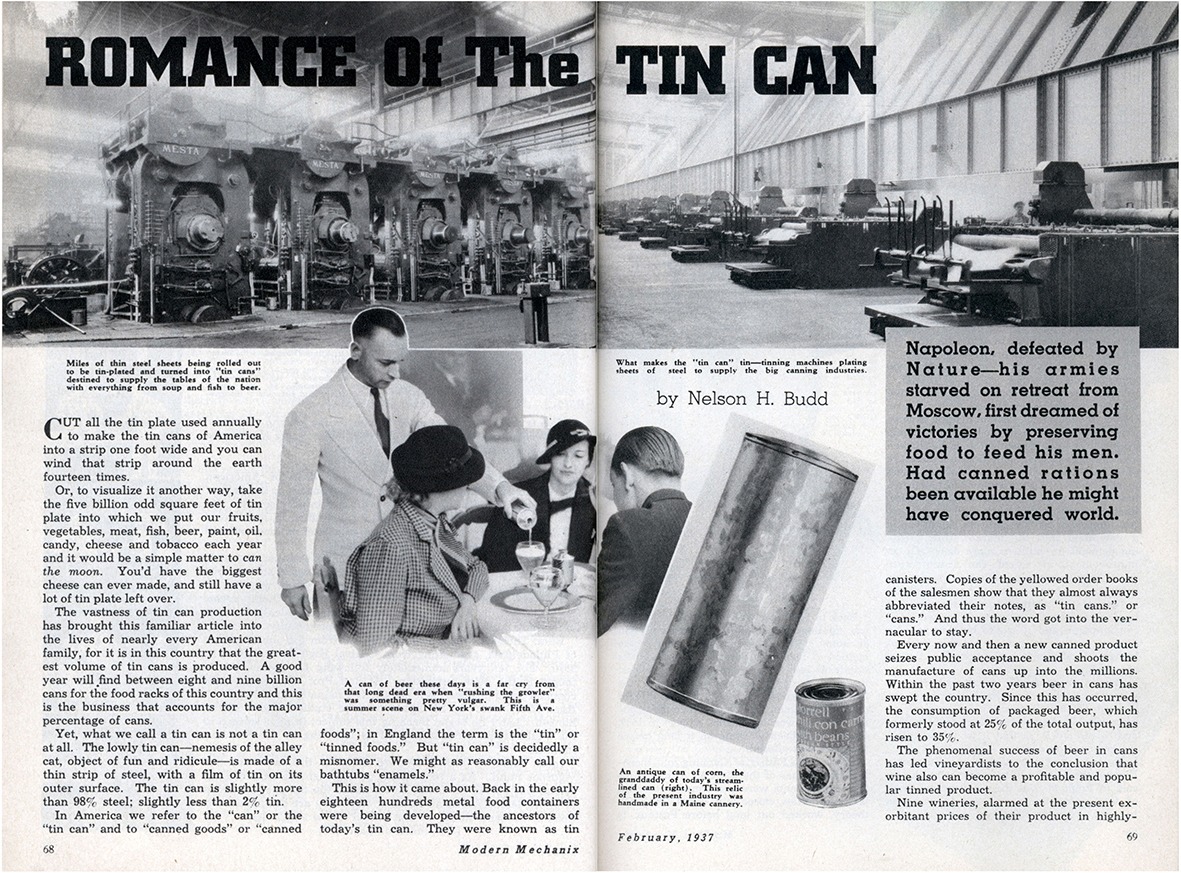

CUT all the tin plate used annually to make the tin cans of America into a strip one foot wide and you can wind that strip around the earth fourteen times.

Or, to visualize it another way, take the five billion odd square feet of tin plate into which we put our fruits, vegetables, meat, fish, beer, paint, oil. candy, cheese and tobacco each year and it would be a simple matter to can the moon. You’d have the biggest cheese can ever made, and still have a lot of tin plate left over.

The vastness of tin can production has brought this familiar article into the lives of nearly every American family, for it is in this country that the greatest volume of tin cans is produced. A good year will find between eight and nine billion cans for the food racks of this country and this is the business that accounts for the major percentage of cans.

Yet, what we call a tin can is not a tin can at all. The lowly tin can ” nemesis of the alley cat, object of fun and ridicule ” is made of a thin strip of steel, with a film of tin on its outer surface. The tin can is slightly more than 98% steel; slightly less than 2% tin.

In America we refer to the “can” or the “tin can” and to “canned goods” or “canned foods”; in England the term is the “tin” or “tinned foods.” But “tin can” is decidedly a misnomer. We might as reasonably call our bathtubs “enamels.”

This is how it came about. Back in the early eighteen hundreds metal food containers were being developed—the ancestors of today’s tin can. They were known as tin canisters. Copies of the yellowed order books of the salesmen show that they almost always abbreviated their notes, as “tin cans.” or “cans.” And thus the word got into the vernacular to stay.

Every now and then a new canned product seizes public acceptance and shoots the manufacture of cans up into the millions. Within the past two years beer in cans has swept the country. Since this has occurred, the consumption of packaged beer, which formerly stood at 25% of the total output, has risen to 35%.

The phenomenal success of beer in cans has led vineyardists to the conclusion that wine also can become a profitable and popular tinned product.

Nine wineries, alarmed at the present exorbitant prices of their product in highly-taxed liquor stores, which have tended to swing purchases in favor or beer and hard liquor, plan to encourage consumption of domestic wine by offering it inexpensively in cans in grocery stores as an adjunct to the home menus.

The entire history of the tin can is dotted with revolutionary occurrences of this nature. In fact, the chronology of can making is completely tied up with the history of canning. The two are inter-dependent, like the chicken and the egg. Which came first, manufacture of canned foods or manufacture of containers to hold them? As a matter of fact, the two have grown to man’s estate, in perfect pace. Each has contributed to the other’s growth. An improved canning process might bring a new food into the market, thus creating demand for millions more cans. Or an improvement in actual can manufacture would in turn make possible new production volume in canned foods. The phenomenal growth of the manufacture of tin cans has been caused by the increase in canned foods consumption, and it works both ways. No history of the tin can is possible without bringing in alongside it, the history of the art of canning.

The tin can is chiefly important because it makes possible what the inventor of the method of food preserving set out to accomplish 140 years ago—a way to cook food and to contain it, so that it would be edible for long periods of time.

The method of preserving food originated in France; the method of manufacturing the tin can, in England; but the development, both of food preservation and can construction to today’s remarkable status, is American.

Back in 1795 nearly every nation in Europe was fighting France and she had revolution at home. The Government needed some method of feeding its armies abroad and its sailors at sea. Scurvy ravaged the sailors; foraging was not always feasible in the Napoleonic campaigns. A prize was offered to the Frenchman who would solve the problem. It was won by Nicolas Appert in 1809, though he’d been working on it long before the prize was offered.

He was the Father of Canning and therefore, the Father of the Tin Can, although his first experiments were performed with glass jars and bottles, closed with corks. Appert’s theory, worked out long before Pasteur, is the theory still followed by commercial canners today. He sterilized the food by heat and he sealed the container hermetically. Though his apparatus was crude and awkward, he was painstaking and thorough, and he perfected a theory, and put it to the test that has proved one of the greatest benefactions to mankind’s comfort and health.

In the fourth edition of Appert’s treatise on his new method of preserving foods he mentions the use of canisters. But the French were poor artisans in tin and Appert had to make them in his own factory. He had tin plate of poor quality and numerous other difficulties, and though he applied his best resources to the problem, Appert’s real contribution was the all important method of processing foods, rather than the invention or development of the container.

While Appert was thus engaged, an Englishman named Peter Durand obtained a patent in 1810 for a tin plate canister. Now we see the first tin can emerging out of history. It was cylindrical, like the one we see coloring our grocery and pantry shelves today, but was made entirely by hand. The raw material was lavishly tinned iron sheet Using shears and a soldering iron, a tinsmith cut an oblong piece of tin, curved it and soldered its ends together to form the body. Then he cut a round piece for the bottom of the can, bending its edges over a circular mandrel, and soldered this on one end. After this was filled with fruit, fish, vegetable or meat, a similar round piece was soldered on the top. A small hole was left in the top so that air could escape as the food in the can expanded while the can boiled. With the can still hot, a drop of solder closed the hole. Sometimes a little globule of this solder dropped down inside the food, but in those days people didn’t mind so much.

With Appert’s method and Durand’s canister, meat was successfully put up for sea voyages. The canning industry had been launched and the can making industry was on its way. Appert, who received a prize of 12,000 francs from Napoleon, had really started four great industries—canning, can manufacture, canning machinery manufacture, and can making machinery manufacture. All these are separate and individually organized enterprises today, though inter-related and interdependent, and all are thriving, carrying out the processes that have defeated Nature’s parsimonious way of parceling out man’s foods according to harvesting seasons and at no other time. The tin can places June foods on the January platter.

The scene now changes to America. William Underwood built a flourishing canning business in New England, after landing at New Orleans and walking all the way to Boston. Thomas Kensett, another immigrant from England, applied for the first American patent on the tin can. Patent officials considered it a hoax and the application gathered dust in a pigeonhole for 10 years. When finally granted the patent was signed by President James Monroe.

Underwood started using tin instead of glass in 1839 but it was still some time before the tin can surpassed the glass container.

During this period of development construction was crude and by hand. An expert tinker could make perhaps 60 cans a day. Jump across the years to the present. In the time taken by that early tinker, whose speed was the wonder and envy of his fellows, to make his 60 cans, today’s automatic machine produces 180,000.

The Civil War furnished the first boom for canned foods, and increased their production so much as to inevitably shoot can manufacture up into volume. About 5,000,000 cans were made at the beginning of the war. By 1870, the output had increased six fold.

And it was at this stage that several inventions of importance in canned foods processing acted to increase the volume of tin cans, even to a greater degree than did refinements in the art of can making itself, which were indeed negligible. Canners were still processing (cooking) by boiling the cans for long periods. A Baltimore canner named Isaac Solomon applied an English discovery to the process. He added calcium chloride to the boiling water. Its temperature was increased to 240 degrees plus. Overnight, the time necessary for sterilization was reduced from five or six hours down to half an hour. The canner whose kettle capacity would produce 1,000 cans was able to turn out 10,000. This occurred on the threshold of the Civil War, in 1861.

That great disturbance gave many people their first taste of canned foods. Soldiers ate them in their bivouacs; sailors on their gunboats; the wounded in hospitals. Canning was no longer confined to the seaboard—to centers around Baltimore and in New England. Canneries sprang up inland—at Cincinnati and Indianapolis. Borden found a market for his canned condensed milk, after having failed for 10 years to put it over.

Improvements and inventions in the field of canning machinery also played their part in this expansion. It wasn’t due alone to processing refinements and the sole outstanding can-making improvement of the time, namely, the invention of capping seals and a furnace with which a young boy could seal twice as many cans as could the master tinsmith with the old style of soldering iron. This inventor was another Maryland canner, Louis McMurray. He also was the first big corn canner, and a new product leaped into the market, one that was destined to become one of the “big three” packs of canning. Last year, corn canners alone used about 264,000,000 cans.

Peas had to be shelled and picked by hand. E. P. Scott and C. P. and J. A. Chisholm perfected a machine that would shell peas from the pod as fast as 1,000 hand workers. Then Scott went a step further and produced the pea viner which, by using a paddle principle, knocked the peas out of pods and sifted them. Nearly 600,000,000 cans were needed last year to hold all the peas packed in America.

Someone discovered and broadcast the fact that tomatoes, or Love Apples as they were called then, were not poisonous. Nearly 648,000,000 cans of tomatoes were put up last year, with another 192,000,000 odd cans of tomato juice on top of that.

A machine was perfected that automatically peeled and cored pineapples. Again, volume production of tin cans soared. Improvements in salmon, in peaches, pears, apples, all had the effect of adding immediately to can production. The cooking time was shortened again when another Maryland cannery – A. K. Shriver – developed the closed kettle. Cooking could be done so speedily that all this automatic machinery had be to perfected so that preparation of food could keep up with canning. Canning technology was improved; the technique of making the can was improved; machinery for both operations was improved.

Better cans now were being made. Dies worked by foot power were introduced. A hole was cut in the top large enough to insert food into the can after the top had been soldered on, with a round disc to be soldered over the aperture, following processing. This was known as the “hole-in-top” can.

The next style was the “open-top.” Tops and bottoms were crimped on without using solder. Thick rubber gaskets made the can air-tight and the crimping of top and bottom was accomplished by folding them over these gaskets.

And then came the most forward step of all – development and perfection of the “sanitary can” – a refinement of the “open-top”-and the can you see all about you today. This generation of consumers never saw anything else.

This can was brought forth in 1896. Charles M. Ams, a chemist, evolved a liquid compound to take the place of the awkward rubber gasket.

George W. Cobb, in Fairport, N. Y., was having trouble getting peaches, pears, and other solid fruit particles filled into the old “hole-in-top” can without mutilating them. He became interested in the Ams can, which, being open at the top, would solve that problem for him. His company, the Cobb Preserving Company, had been manufacturing its own cans since it was founded in 1875. This youthful manager of production installed the Ams apparatus in his plant.

In 1902 and again in 1903 his results were convincing enough to warrant the formation of a company the following year devoted to the manufacture and distribution of sanitary cans. Can making was started in a building at Fairport in July, 1904. Eight million cans were made the first year. In three years a branch plant went up in New Jersey and another in Indianapolis; later a plant at Niagara Falls, Ont. These were purchased in 1908 by the American Can Company.

The sanitary can was unquestionably the chief factor in bringing tin can production to its present figure of astounding magnitude, and it was the last achievement of revolutionary aspect in the history of the tin can.

Lacquers, enamels and lithography have come along to adorn and beautify cans but their chief value has always been and always will be their practicability, utility and convenience. The perfect vessel for food-they cook and they carry, achieving Appert’s dreame-to keep foods edible over long periods of time.

ROMANCE Of The TIN CAN