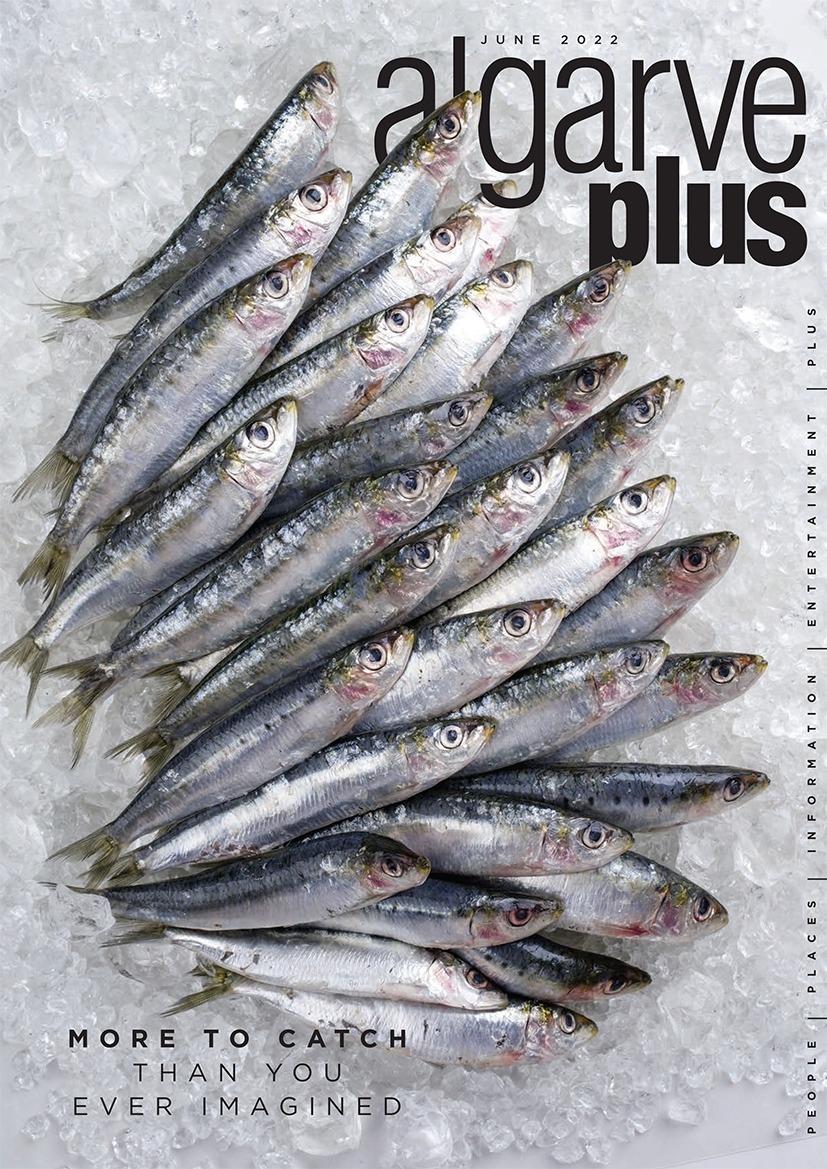

Algarve plus magazine - June 2022

CENTURIES BEFORE THE ALGARVE BECAME A DREAM PLACE TO START A NEW LIFE CHAPTER, LOCAL FISHERMEN WERE CHALLENGING THE WATERS AND BUILDING WHAT WOULD BECOME A KEY INDUSTRY. THERE’S MORE TO SARDINES THAN A BARBECUE LUNCH

Words: BRIAN REDMOND

Images: MUSEU DIGITAL DA INDÚSTRIA CONSERVEIRA

In 1965, the Algarve was about to be changed forever as a result of an ambitious directive handed down by Salazar three years earlier. He decreed that an airport should be built in Faro exempting it from “the approval of the Court of Auditors and from administrative formalities” – in other words, planning permission. And so it was that on 11 July 1965, the President of the Republic, Américo Thomaz, travelled to this remote region of the country to inaugurate the new airport. He was greeted enthusiastically by the local population of São Brás de Alportel where he stayed, and by the crowds who gathered at the airport to witness the pomp and ceremony.

A popular piece of urban mythology that came from the ceremony was that upon the President’s arrival in an open-topped car, a woman in the crowd exclaimed: “Look at the ice-cream man moving among all the police!” because the President was dressed in his full white uniform as admiral of the fleet, and his entourage that swarmed around the car were in full military uniform.

Despite the case of mistaken identity, the day proved to be a pivotal point in the fate of the Algarve, which had long been forgotten by the ruling elite and dismissed as an outback more akin to Africa than to the Portuguese motherland. With the arrival of the airport, investment into mass tourism could begin in earnest.

On the beach

Monte Gordo, Lagos and Praia da Luz became the most popular destinations in the early days with Portimão (Praia da Rocha) and Albufeira soon overtaking them. Images from that era showed interaction between the sun-worshipping beach bathers mingling with the local fishermen who were going about their daily lives. It was a romantic and exciting image of northern European holidaymakers ‘discovering’ a hidden corner of the continent.

Fishermen and their unique skills had been the primary commercial activity in the region for centuries, going back to Roman times when a by-product known as garum, a fermented fish sauce, was much sought after as a delicacy in Rome. It is a source of umami flavouring, with a savoury taste similar to soy sauce. It was made from the intestines of big fish, like tuna, or whole small fish such as sardine and mackerel, combined with salt. The liquid that formed at the top was ladled off and sold separately from the leftover remains of the fish, called allec, which was used by the poorer classes as an accompaniment to maize dishes.

The best quality garum could realise huge prices. There were factories producing the material, particularly on Ilha do Pessegueiro on the western Alentejo coast, and further north at Tróia on the estuary of the Sado River, which was the largest centre for the production of garum, and also salsamenta, and in the world. From there, it was exported from Lacobriga, modern day Lagos, to the Roman empire.

For many tourists, sardines, whether from a grill on in a can, are synonymous with Portugal. But it is cod that is exalted nationally and is called nosso fiel amigo or ‘our faithful friend’ because it has looked after the needs of the population through good times and bad for many centuries. But while cod and salted cod, bacalhau, with its reputed 1,000 recipes, is the King of Fish through most of Portugal, in the early part of the 20th century, tuna was the Emperor of Fish in the Algarve.

The right time

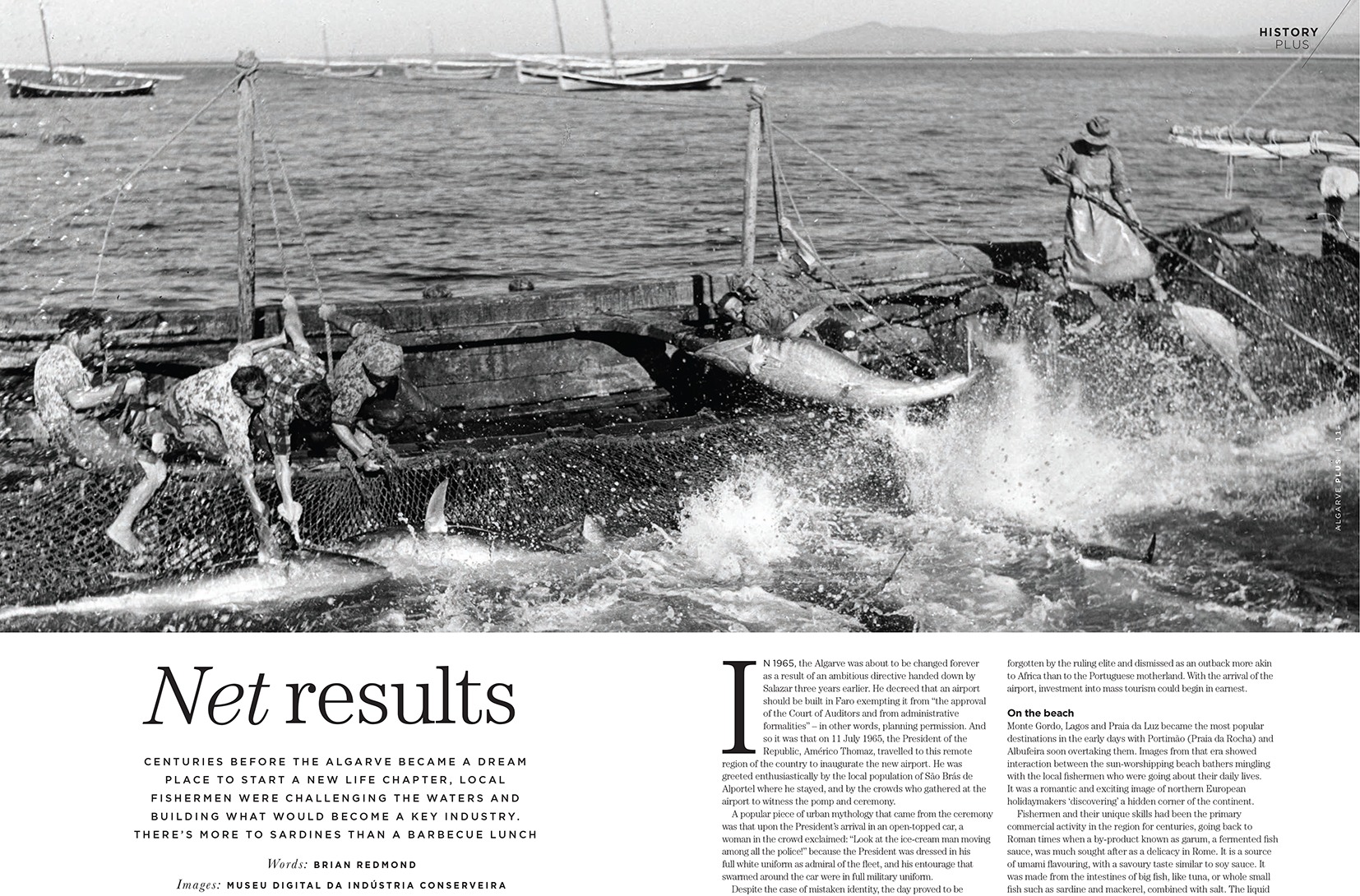

Then, as fleets of fishing boats made their way from the western ports of Peniche, Matosinhos and Sines across the vast and treacherous north Atlantic to reach the fertile cod grounds off the Grand Banks of Nova Scotia, the fishermen of Sagres, Alvor, Portimão, Albufeira, Quarteira, Olhão, Monte Gordo and Vila Real de Santo António lay in wait for the annual breeding migration of tuna from the Atlantic Ocean into the Mediterranean Sea. The physical effort of catching the Blue Fin Tuna on their migration was extraordinary, and involved literally hundreds of men.

A visit to Barril beach near Tavira, with its own rail-road and workmen’s cottages, plus the hundreds of anchors used in mooring the trap nets standing on the beach (it took 16 men to lift each one) will give you an idea of the amount of toil that went into the tuna fishing industry.

Formal counts of the eastern Algarve fisheries began in 1876, and continued until 1972. Officially, there were 23 ‘traps’ that would operate annually at this time. Each was made up of a network of wall nets that

were sited across hectares of ocean, and would channel the fish into a central capture zone. The trapping was separated into two periods, defined by the migration of the fish, ‘inward’ (April and May) and ‘outward’ (July and August). The outward migration usually proved to be more successful. The grade of fish ranged in weight from 5kg Cachorretitas to 150kg Atum that grew up to two metres in length.

Because the fish migrate in random patterns, it was always difficult to site the traps so, for example, from a high in 1906 when an astonishing 92,000 fish were caught from 16 traps, to one fish from one trap in 1971, and then in the final year, 1972, when wall nets were made illegal, the same one trap yielded 4,800 fish.

Naturally, enormous wealth was generated by the tuna, and canning factories from Vila Real de Santo António in the east to Lagos in the west, reaped the benefits. Conservas Ramirez was founded in Vila Real de Santo António in 1853 by Sebastian Ramirez, a Spaniard, who formed a business salting and canning tuna. In 1865, he adopted the canning conservation method developed by Frenchman Nicholas Appert, whereby food – be it fish, fowl, meat, fruit or vegetable – was packed into hermetically-sealed containers and ‘cooked’ at 100˚C. Today, the Ramirez family produces more than 50 million units per year and exports throughout the world.

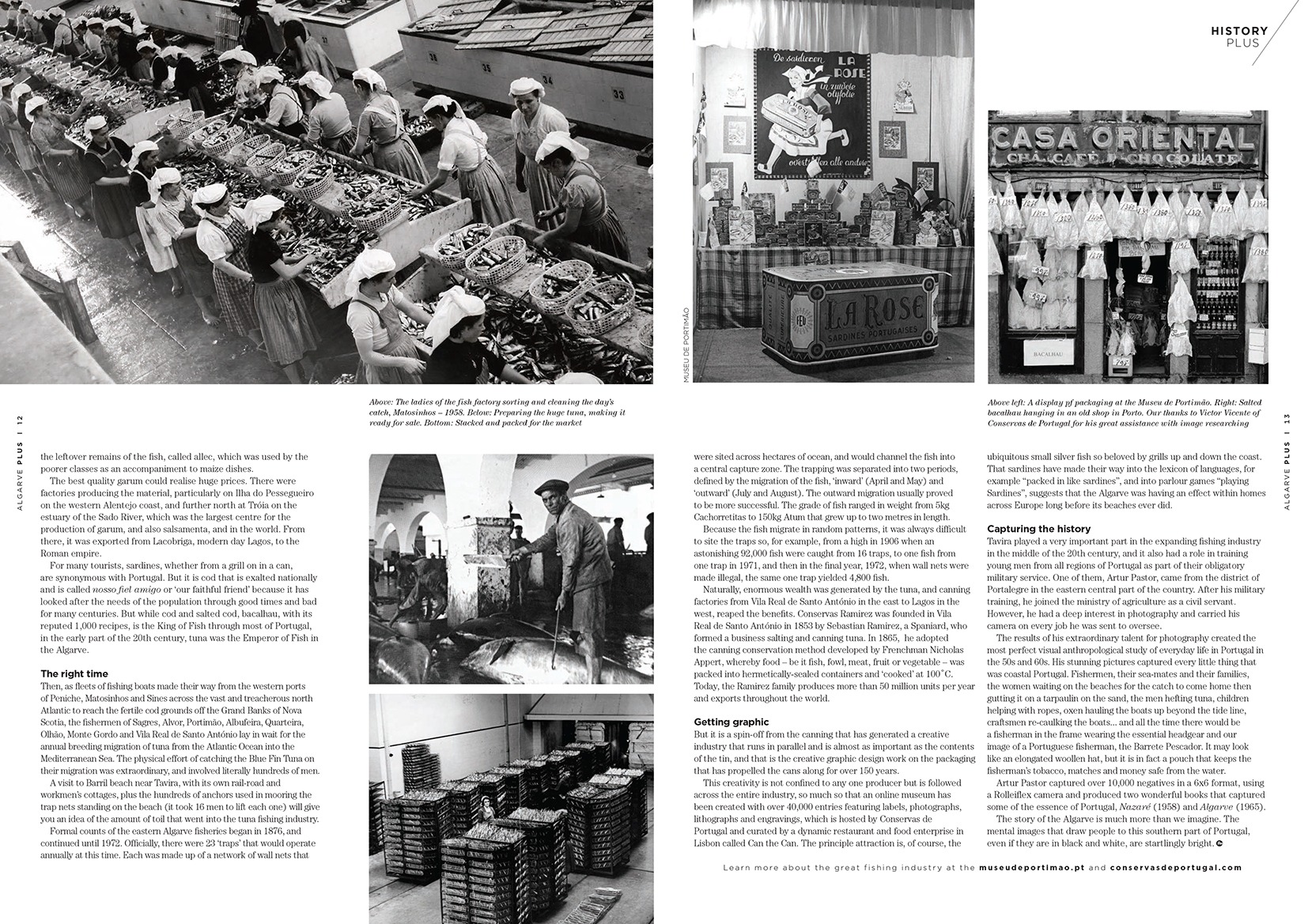

Above: The ladies of the fish factory sorting and cleaning the day’s catch, Matosinhos – 1958. Below: Preparing the huge tuna, making it ready for sale. Bottom: Stacked and packed for the market

Above left: A display pf packaging at the Museu de Portimão. Right: Salted bacalhau hanging in an old shop in Porto. Our thanks to Victor Vicente of Conservas de Portugal for his great assistance with image researching

Getting graphic

But it is a spin-off from the canning that has generated a creative industry that runs in parallel and is almost as important as the contents of the tin, and that is the creative graphic design work on the packaging that has propelled the cans along for over 150 years.

This creativity is not confined to any one producer but is followed across the entire industry, so much so that an online museum has been created with over 40,000 entries featuring labels, photographs, lithographs and engravings, which is hosted by Conservas de Portugal and curated by a dynamic restaurant and food enterprise in Lisbon called Can the Can. The principle attraction is, of course, the

ubiquitous small silver fish so beloved by grills up and down the coast. That sardines have made their way into the lexicon of languages, for example “packed in like sardines”, and into parlour games “playing Sardines”, suggests that the Algarve was having an effect within homes across Europe long before its beaches ever did.

Capturing the history

Tavira played a very important part in the expanding fishing industry in the middle of the 20th century, and it also had a role in training young men from all regions of Portugal as part of their obligatory military service. One of them, Artur Pastor, came from the district of Portalegre in the eastern central part of the country. After his military training, he joined the ministry of agriculture as a civil servant. However, he had a deep interest in photography and carried his camera on every job he was sent to oversee.

The results of his extraordinary talent for photography created the most perfect visual anthropological study of everyday life in Portugal in the 50s and 60s. His stunning pictures captured every little thing that was coastal Portugal. Fishermen, their sea-mates and their families, the women waiting on the beaches for the catch to come home then gutting it on a tarpaulin on the sand, the men hefting tuna, children helping with ropes, oxen hauling the boats up beyond the tide line, craftsmen re-caulking the boats… and all the time there would be a fisherman in the frame wearing the essential headgear and our image of a Portuguese fisherman, the Barrete Pescador. It may look like an elongated woollen hat, but it is in fact a pouch that keeps the fisherman’s tobacco, matches and money safe from the water.

Artur Pastor captured over 10,000 negatives in a 6×6 format, using a Rolleiflex camera and produced two wonderful books that captured some of the essence of Portugal, Nazaré (1958) and Algarve (1965).

The story of the Algarve is much more than we imagine. The mental images that draw people to this southern part of Portugal, even if they are in black and white, are startlingly bright.

Learn more about the great fishing industry at the museudeportimao.pt and conservasdeportugal .com