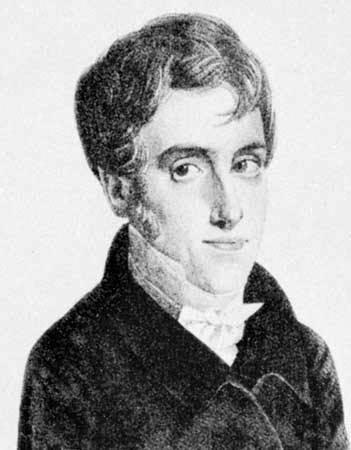

Nicolas Appert

Also known as Nicolas-François Appert

born c. 1750 Chalons-en-Champagne, France

died June 3, 1841 Massy, France

Nicolas Appert (1749-1841) may not have understood the science behind food preservation, yet his canning process is directly responsible for the multitude of prepared foods that sit on grocery store shelves around the world.

Nicolas Appert was born on November 17, 1749 at Chalons-sur-Marne, France. The son of an inn-keeper, he received no formal education. He had an interest in food preservation and, at an early age, learned how to brew beer and pickle foods. Appert served an apprenticeship as a chef at the Palais Royal Hotel in Chalons, France. In 1780, he moved to Paris, where he excelled as a confectioner, delighting customers with his delicious pastries and candies.

Inspired by War

During the late eighteenth century, Napoleon Bonaparte expanded his quest to conquer the world. As French troops invaded neighboring countries, it soon became apparent to the government that world conquest would not be within its grasp without the ability to carry foods for an extended time without spoilage. The executive branch, known as the Directory, offered a prize of 12,000 francs to anyone who could develop a practical means of preserving food for the army during its long forays.

Appert began a fourteen-year quest, determined to win the prize. Chemistry at this time was a little known science and there was virtually no knowledge of bacteriology. Appert’s experiments on the preservation of meats and vegetables for winter use was conducted through trial-and-error. He had little reference on which to rely since there was only one published work on food preservation through sterilization, written by Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799). Appert based his process on heating foods to temperatures in excess of 100o C (212o F), the temperature at which water boils. To do this, Appert used an autoclave, a device that uses steam under extreme pressure to sterilize foods.

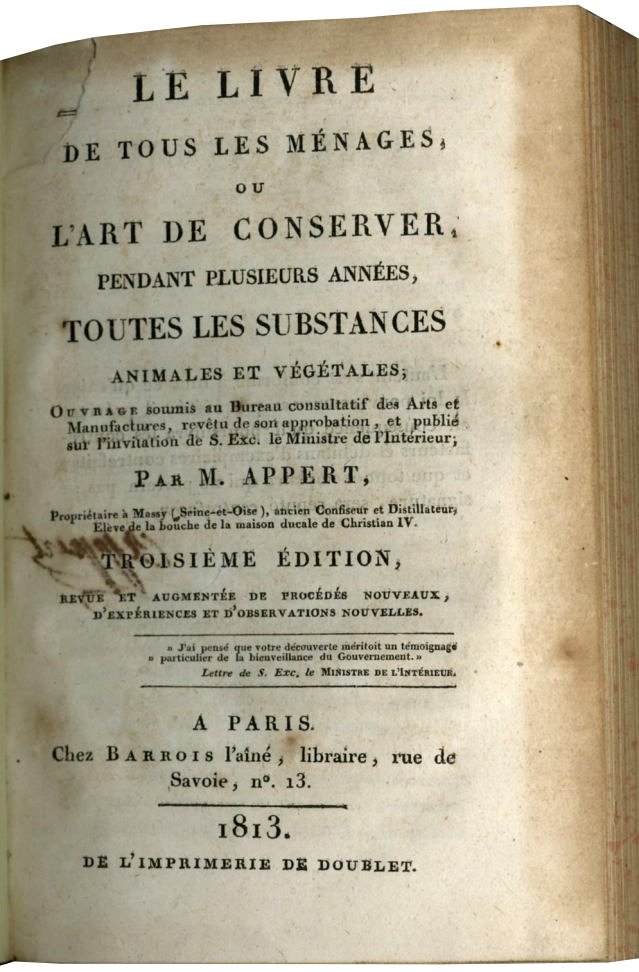

In 1804, Appert opened the world’s first canning factory in the French town of Massy, south of Paris. By 1809, he had succeeded in preserving certain foods and presented his findings to the government. Before awarding the prize, the government required that his findings be published. In 1810, he published Le Livre de to us les Menages, ou l’Art de Conserver pendant plesieurs annees toutes les Substances Animales et Vegetables. (The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years). Upon publication, the Directory presented him with the 12,000 franc award. His work received critical acclaim and a gold medal from the Societe d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale. (Society for the Encouragement of National Industry.)

The entire process was time consuming, taking about five hours to complete the sterilization. It involved placing food in glass bottles, loosely stopped with corks and immersing them in hot water. Once the bottles were heated, they were removed and sealed tightly with corks and sealing wax, then reinforced with wire. Appert demonstrated that this process would keep food from spoiling for extended periods of time, provided the seals were not broken. It was used to preserve soups, meats, vegetables, juices, various dairy products, jams, jellies, and syrups. Although Appert could never explain why his food preservation process succeeded, he is, nevertheless, credited with being the father of canning. It would be another half century before his countryman, Louis Pasteur, explained the relationship between microbes and food spoilage, further validating Appert’s basic processes.

Appert used his winnings to finance his canning factory at Massy, which continued to operate for another 123 years, until 1933. When canned foods were studied in England, it became apparent that glass bottles posed a problem because of breakage.

In 1810, Peter Durand patented metal containers. Twelve years later, Appert advanced his process from the use of glass jars to cylindrical tin-plated steel cans.

This innovation increased the portability of food for both the English and French military.

In addition to perfecting the autoclave, Appert was responsible for numerous inventions, including the bouillon cube. He also devised a method for extracting gelatin from bones without using acid. Despite his success in the field of food preservation and the recognition he received from his government, Appert died in poverty on June 3, 1841 in Massy, France. He was buried in a common grave.